As I sit down in Gary Stewart’s office, break out my laptop and recording device, and begin to interview Stewart, I notice that his office was pretty much empty. He had two photos framed on his wall but other than that, it was just his desktop, his desk, and himself.

Most Stevenson coaches deck their offices with tons of different memorabilia from championship plaques to family photos to perhaps a bobblehead. I took a mental note of Stewart’s office, but I was not going to interrogate him about it. The Spartan nature of the walls tells me this is a humble man, one who doesn’t trumpet his myriad successes, a man who’d rather point to the task at hand, the next practice, the next game.

I didn’t go to his office on January 18, 2024, for that conversation. I wanted to write a feature article on Stevenson’s all-time wins leader for men’s basketball, cataloging his long and historic career coaching college basketball. My goal was to interview him to get to know him more and for him to reflect and talk about his long list of achievements and accolades.

Now, I had never met Stewart before and seeing how active I have been with Stevenson athletics as The Villager’s sports reporter, I was surprised it took me this long to meet him. I didn’t know him as a person like his players and colleagues do.

Personally, I expected a brief productive 15-minute interview with Stewart. Well, 15 minutes ended up being some of the most memorable 60 minutes of my life.

As I settle in, we talk briefly about recent times for his team and how they are battling the injury bug. I knew at the time that my good friend, guard Cameron Sapienza, was dealing with a leg injury, so we talk about him and how big of a deal his absence on the court is. I briefly mention that he and I graduated high school together in 2020. I mention Mount Saint Joseph High School in Baltimore, Maryland.

“Coach Clatchy!” he excitedly says, referring to the head basketball coach at MSJ, another giant in basketball much like Stewart. Absolutely, he has recruited many of Clatchy’s players to Stevenson before. “That’s a name! What an amazing coach,” he continues. We both smile and quickly discuss Clatchy’s legacy at MSJ.

The interview begins. First, I want to know about Gary Stewart before Stevenson and before his time as the president of the National Association of Basketball Coaches. I ask him about how he began with the game of basketball, and he takes me back to his elementary school days. He has spent almost his entire life surrounded by basketball, and his journey into coaching the game began a lot earlier than many may think, as early as sixth grade to be exact. A serious foot injury kept Stewart from playing basketball early in elementary school, but he still surrounded himself with the coaches during practices and learned through what they did.

Stewart sits back comfortably in his chair, speaking to me with calmness and intelligence in his voice.

“I learned the game through a different perspective,” he said. “Not necessarily by doing, but what we would deem as a lecture. [I was good at] retention of information back then as related to sports and I got more and more enthralled with not only basketball, but with sports in general.”

During high school, Stewart was cleared to play basketball without restriction and played in many youth camps and clinics. His passion for the game and desire to coach only skyrocketed from there. He would eventually begin traveling to camps at different universities and getting opportunities to do some instructional coaching at them as well. He was in awe of the coaches present at the camps.

“Outstanding coaches,” he said. “They really spring boarded my passion [for basketball] if you will to greater heights.”

Stewart recalls how someone once told him to “walk with elephants.” He interacted with some of the greatest high school and college coaches in the country, certainly walking with some giants of the game during his time.

“I always had a thirst to learn,” he said of his younger self. “I felt like I got a wide range of how to do things, how people do things, and how they taught.”

Stewart graduated from Division III La Verne College (now the University of La Verne) in La Verne, California. Though he found his stride on the court as a player in high school, he elected not to play collegiately as he was trying to figure some things out for his future. It was during his college years that he became ready to get going as soon as he could in his coaching career, and his coaching career started almost immediately after he graduated from La Verne.

Stewart talks about how he returned to his alma mater to coach following graduation. At age 24, he became the youngest head coach of a four-year university in the United States.

That’s where his iconic coaching career began. That is where it all started.

Stewart spent nine seasons with La Verne from 1987-1995. Under his guidance, the Leopards won three Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference championships and were nationally or regionally ranked six times. After leaving La Verne, Stewart was the head coach at Cal State East Bay from 1995 to 1997, taking the team from last place to first place in just two seasons. He spent two years as an assistant coach at UC Santa Barbara from 1997 to 1998, and returned to a head coach position at UC Davis from 2003 to 2011. UC Davis was below .500 prior to Stewart’s arrival, but went 18-9 in their first season with Stewart at the helm. In 2009, while with Division I UC Davis, Stewart was elected to La Verne’s athletic hall of fame.

Eventually, the DI lifestyle took a toll on Stewart, and he admitted that he hit many rough times as he struggled to manage life and work at UC Davis. He began seeking DIII coaching opportunities.

“I gained 10 pounds a year and I had been [at UC Davis] for eight years,” he said. “That’s kind of like a cul-de-sac, and it does not end well. It is easy to spell that out, and people can see the conclusion of that story; there’s going to be a heart attack or something. I felt like I needed to reassess things, and in that reassessment, I realized that I really enjoyed basketball. It wasn’t something that I wanted to get rid of, but I was not handling stress as well as I needed to.

“I needed to get that under control,” he continued. “I just loved the work-life balance of small college basketball, so I longed to get back to that.”

Stewart reached out to numerous sources about Division III coaching jobs and found an opening at Stevenson University. His research led him to visiting campus and falling in love with Stevenson, which led to meeting with Athletic Director Brett Adams and other athletic personnel. At the time, Adams was stepping down as SU’s head men’s basketball coach and was searching for his replacement.

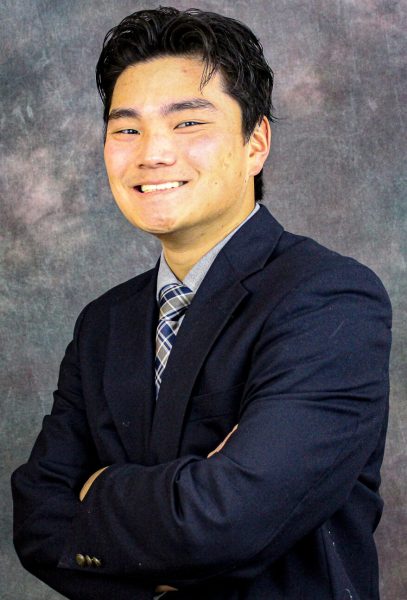

In 2011, Stevenson named Stewart as the second men’s basketball head coach in program history. He has since then also become an assistant athletic director in the university’s athletic department, a position that he still holds to this today.

Since Stewart’s arrival, Stewart has led the Mustangs to two Eastern College Athletic Conference championships, in 2014 and 2015. The Mustangs have also made two appearances in the Middle-Atlantic Conference championship game in 2014 and 2015. His team received votes for the D3hoops.com’s list of Top 25 teams in both seasons and after finishing 21-8 in the 2013-2014 season, Stewart was named the MAC Coach of the Year. In addition, the Mustangs’ first win of the 2023-2024 season marked history for Stewart, making him the all-time winningest men’s basketball coach at Stevenson. He passed Adams’ previous record of 138.

It has been a successful stint as a Mustang for Stewart. It has been a memorable coaching career as a whole from La Verne to now. Even after all of his many accomplishments, he centralizes his career around the idea that this journey has been more than about him.

Without me even asking, this is where he begins to discuss the appearance of his office.

“The only reason I have these pictures up is because [the administration] told me that I need to have something up,” he said with a slight laugh. “It looks like I’m moving out when a recruit comes.” He followed that with a quote from Major League Baseball great, pitcher Satchel Paige. “He said ‘don’t look back. Someone might be gaining on you.’ I’m not one to stare at awards, though I am very appreciative of the things that I’ve been able to accomplish with others in this game.“

“But that’s not why I do it,” he continues. “It’s always been about the student-athlete. It’s his experience, and I don’t want to get in the way of that. I want to enhance it, and I want them to invest in their dreams and aspirations.”

Stewart wanted me to understand that he has not worked alone in all that he has accomplished.

“Everything I do is part of a team, part of a group,” he said. “Sometimes I get credit for things. Maybe because I’m the figurehead or I’m easy to identify. There is a village of people here [at Stevenson] that are here to help and support students. I feel like I need to do my part, and we all rejoice when they wear a cap and gown and go across the stage.” Graduation day is his favorite day of the year at Stevenson. “I haven’t missed one. It’s life changing for a lot of student-athletes. It’s a special, special day.”

Another part that he enjoys about his job is seeing what his student-athletes become long after they have departed Stevenson University.

“I am so incredibly proud of the kind of young men that the student-athletes under my hospice have become,” he said, “how they contribute to their families and their communities. I’ve coached folks that are doing unbelievable things in every walk of society, whether they are in law or in the medical fields, in athletics working on university campuses.“

I would have thought he’d mention the ECAC championships or his record-breaking win this season as some of his favorite moments. To hear him say that graduation day is his unanimous favorite day hit me on a different level. I’m now beginning to realize how much Stewart cares and his reasoning behind doing what he does.

When asked if this is what he pictured for the program and for himself when he arrived at Stevenson, he responded with a completely selfless and heartfelt answer.

“This has never been about me,” he said. “I have a job and every time I go through the door to enter the gymnasium, I’m going to meet a group. I’m a part of a special, special fraternity. So it’s never really been about me. I might have both hands on the steering wheel as the head coach in the driver’s seat, but I got a lot of folks in the vehicle and we take the journey together. It’s not separate. We are all in the same vehicle together.”

“I’ve never looked at it like ‘I’ve accomplished this’ or ‘I did this,’” he continued. “I’ve always looked at it as ‘Stevenson achieved this’ and ‘Stevenson achieved that.’”

Stewart has embraced his lengthy time as a Mustang, and is very thankful to be where he is.

“It’s a longevity award,” he said. “It’s a good place to work, it’s really a great place and fit for me. I love the people here, and I love the students I’ve worked with.”

By Stewart’s side in his efforts to build the men’s basketball program at the university is Adams, who passed the torch down to Stewart on the court. Stewart is very thankful and grateful for what Adams contributed, especially prior to his own arrival in 2011.

“He started the program, and it is amazing what he has accomplished,” he said of Adams. “He had outstanding teams, some NCAA tournament teams. I just wanted to carry on with the great work that he had started here. The program was very well thought of in the basketball community, and that’s a testament to Brett and his undying, relentless pursuit of excellence. He was able to grow an intercollegiate basketball program out of his front pocket and form a formidable team in the Mid-Atlantic region.”

Whether he is teaching basketball or life, Stewart sees himself as a teacher.

“There are people that teach chemistry, there are people that teach biology, English, and art. I am fortunate enough to be a guy that teaches collegiate basketball. The general public sees the 40 minutes of the duration of a basketball game. There is so much more than that.”

“I always see myself as a teacher, and the basketball court is my classroom,” Stewart continued. “There are so many lessons that are applicable to life.”

Stewart keeps his players in check with life beyond basketball by engaging them with the community. He has taken players into the public to feed the homeless and read to elementary schools and engage with organizations such as Autism Speaks and Coaches Versus Cancer, whom Stewart is associated with as an active member.

As we near the end of the interview and as I run out of questions, Stewart’s voice and posture remain the same: confident and intelligent. The look in his eyes as he spoke to me depicted the image of a man who means what he says and is not done teaching and will not be for a long time.

With a slight laugh and a smirk, Stewart jokingly states that he can’t believe that Stevenson “pays me to do this.” He is being paid to do what he loves doing, and that is teaching. His occupation surrounds him in the game that he has always loved and raised himself on, and that is basketball.

“It’s a labor of love,” he said. “If you’re ready to play basketball right now, I’m ready.” At this point, the interview has become a conversation between him and I. I no longer feel that I am interviewing Coach Stewart, but sitting in his presence simply conversating with him and absorbing his knowledge. “Think about where we started this conversation, [talking about] a love of the game and chasing that passion. I’ve never gotten away from that. I’m literally four steps away to a gymnasium, and that’s my happy place. Some people like this beach, some people like this particular city, town, or country they visited. My happy place tends to be a basketball court.”

“It’s been an unbelievable journey,” he said towards the end of the interview. “But I’m in the middle of the ring [right now] and I’m still swinging.”

Yes he is. His journey is far from over.

The interview ends, but our time together that evening does not. I thank Stewart for bringing up Satchel Paige’s quote because I was inspired by the idea of moving forward and working hard to advance on the person competing with you.

“Do you ever notice that the front windshield on vehicles are bigger than the bac windshield?” he asked me. “Why do you think that is?” Pause. “Keep focusing on the front windshield.” That is, the bigger windshield full of greater opportunities ahead.

“We’re just two baseball fans sitting in this room, passionate about the game,” he added.

“Ah, so you watch baseball too?” I ask, excited.

“Oh, I love baseball,” he says. He and I then go on about his favorite team, the California Angels. I love how he addressed them as the California Angels. They are the Los Angeles Angels today, but he stuck true to his team from the past as the California Angels and the icons that he saw play them, most notably slugger Tim Salmon. He and I talk about my association with baseball, then going about Stevenson club baseball thanks to me wearing my team’s hoodie that day.

When we talk about baseball, he has a look of happiness and peace on his face, though a more disappointed look when we discuss the current situation of the Angels which is, to say the least, abysmal.

“I’m going to come see you play one day,” he said. “I talk to [club sports director] Matt Grimm a lot, so I’m sure he and I can make that happen.”

Wow, Gary Stewart told me that he wanted to see me play baseball. I never thought in a million years that a widely-recognized college basketball coach would tell me that he wants to see me play baseball.

Stewart then pulls out three random questions and quizzes me on several different topics including the cartoon character Popeye’s rise to stardom in the cartoon world and the invention of the Chevrolet Corvette. Of course, I did not get any of the answers to his questions right but if people ask me how I learned those facts about Popeye and Chevrolets, I can tell them that Gary Stewart taught me that while I was at Stevenson University.

I was mind-blown! I was amazed at all the things he was sharing with me. He is feeding me all of this incredible knowledge and facts, and I’m sitting across from him, shocked and mazed while absorbing everything that he is saying. Let me reiterate that we had only just met not even an hour ago.

“You’re a big baseball guy, so I’m going to read you something,” he tells me. He takes his time pulling up the story of 17 inches as I get comfortable in the couch I was sitting in.

Oh I’m in for a treat, I thought, already blown away at our meeting thus far. He’s doing this for me! We were supposed to be done a while ago, but he’s literally doing this for me! We’ve only known each other for not even an hour!

I slide my phone under my bag and prepare to focus and listen to the story. Stewart pulls it up on his desktop and reads me the story. He does not rush through it, but he slowly and clearly reads me the story of the 17-inch home plate, almost as if he made sure that I walked out of his office taking something away from the article. We both shared the same goal: I walk out learning something valuable.

In 1996, Chris Sperry attended the American Baseball Coaches Association conference in 1996. John Scolinos was the name of the day, and Sperry could not figure out why. Scolinos took the stage wearing a necklace holding a full 17-inch wide home plate on it. He did not mention why he wore a full-sized home plate until the very end of the speech.

Home plate is the same width across all leagues of baseball from little league to DI college baseball to the big leagues. He goes on to say that nobody will widen home plate and make pitching easier if a pitcher cannot throw a strike and hit his target. This correlates to the idea that we should not curb the rules (aka widen home plate) just to make things easier for one individual or for a group of people. Scolinos discusses that areas such as the country’s school system and the church are struggling because too many people are curbing the rules.

There is a failure uphold a higher standard and advance in the world because they manipulate the situation, and they curb those 17 inches. As Scolinos says, if we fail to hold ourselves to higher standards and to our own accountability, then the world becomes much darker just like the black rubber back of home plate. Scolinos’ message to the coaches in the audience is whether it is on or off the field, to stay within 17 inches.

As mentioned earlier, he is always teaching more than just basketball. He concluded our meeting my telling me this.

“Do something for me,” he told me. “Stay within 17 inches.”

So there you go. What I thought was going to be a quick 15-minute interview turned into 60 minutes that I wish had lasted longer. Gary Stewart truly is a giver and a teacher. Basketball is a major part of what he teaches but he is a great teacher of life. He cares about and mentors everyone he encounters, whether he knows them to heart like his players and co-coaches or he just met someone like me on late notice.

I may not play for him on Stevenson men’s basketball, but whenever I run into him, I will acknowledge him in my mind as not just the winningest coach of all time at Stevenson University, not just a La Verne hall of famer, but also a life coach who can give someone a completely new outlook in life within minutes. If you were to spend an hour with Stewart like I did, you might say the same thing.

That’s who he is. He is a giver. He is a teacher.

Ladies and gentlemen, Gary Stewart.