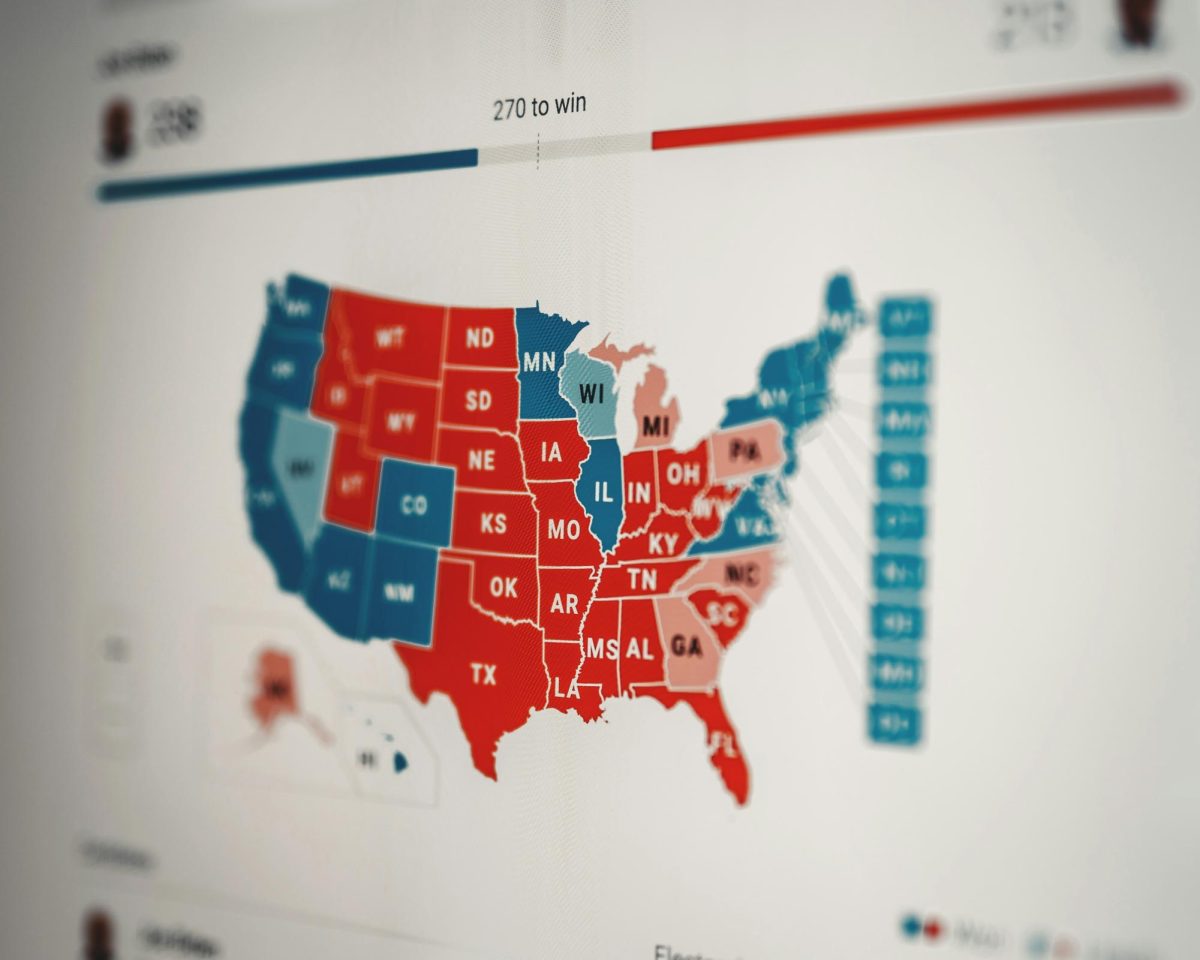

In the era of fake news and Russian bots, media literacy has become a sparse yet essential skill set. The term fake news has become a household phrase after the 2016 election, yet its definition is a hotly debated topic.

In the era of fake news and Russian bots, media literacy has become a sparse yet essential skill set. The term fake news has become a household phrase after the 2016 election, yet its definition is a hotly debated topic.

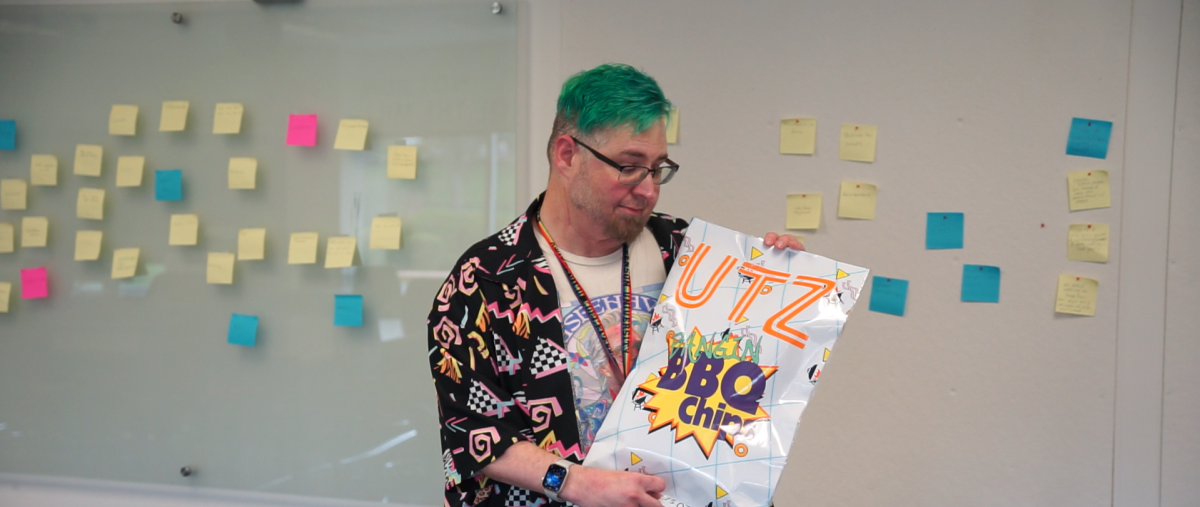

Professor Gerald Powell of the business communication department, who currently teaches a special topics course called Introduction to Mass Media, defines fake news as news that does not have the interest of the people participating in society, and attempts to distract.

According to Mitchell et al., four in 10 Americans get their news online while 50 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 get their news online. Furthermore, only 27 percent in this age group watch TV news while a miniscule 5 percent read newspapers. But online news isn’t always reliable. And given how easy it is to spread information online, this creates a perfect environment for misinformation to thrive. When confronted with any new information, online or otherwise, the consumer of the information must take steps to determine its validity. Otherwise, they inadvertently spread misinformation and become a propaganda piece for potential bad actors.

The National Association of Media Literacy Educators defines media literacy as the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication. Powell added, “Media literacy teaches us how to figure out what information is credible and not credible. That is, what information is helping me participate in the country, city, and community I live in.”

Powell made a point to refer to the news audience as consumers, and explained that all purveyors of news are trying to sell their own biases to the audience. “We’re bombarded with 8 million pieces of information per second. A lot of this is happening on a subconscious level. The idea that you’re not consuming is a myth. We (humans) are gluttons for information,” Powell said. In essence, news sources are salesmen, and they target the audience as a potential buyer.

To better understand the purpose behind new information, a media literate person determines the media messages and media effects of information. Media messages are the text and subtext, or the content and its meaning, in within the story and its format. Media effects are how stories influences current trends, and their consequences.

When confronted with new information, whatever form it may take, the consumer should ask themselves the following questions:

1. What information am I being exposed to?

2. Where did this information come from?

3. Why is this information being spread?

According to Gabielkov, Ramachandran, Chaintreau, & Legout, 59 percent of links shared online weren’t opened by the people who shared them. Information cannot be processed without analysis. Regardless of how unbelievable or convincing a title may sound, the entire content must be read and fact checked before believing in it or sharing it.

The next step, identifying where the information originated from, means looking at the source. What sort of information does this source regularly put out? And have they released information which has been debunked in the past? Powell also expressed the importance of checking what advertisements the news source puts out. As Powell put it, “Someone has to pay the bills for the (news) producers. That becomes the backers for the news.”

Finally, the third question demands people to look at why the source is putting out this information. Is this source trying to share information to educate the public? Is the source trying to sway public opinion in a certain direction? Or is this source speaking on behalf of the entities which pay it to advertise their products on its platform?

These questions can and should be asked of all news sources, be they articles found on Facebook or CNN broadcasts. The information we digest paints our world view, which affects the decisions we make on a daily basis. It is important to understand these design behind media if we want to be free of the influence of bad actors.