SAFE HARBOR?

Clean water is essential for those using Baltimore’s Inner Harbor for recreation

BALTIMORE — Sunshine reflects off the current of the Inner Harbor at Bond Street Wharf. A man paddles in a red kayak, a neon yellow life vest strapped to his chest. Waterfowl traverse the harbor in pairs: two female mallards dip under an overpass and swim toward floating wetlands. Water taxis carry tourists and residents from Under Armour HQ to Canton Park, and in the distance, an anthropomorphized “trash wheel” collects waste and debris. Everything moves at an unhurried pace, far removed from the bustle of the city.

This idyllic scene is in major part due to the work of a network of nonprofit and governmental agencies tasked with improving the water quality of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and other waterways. One such organization, Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, is focused on getting these waterways to a very specific goal — to be swimmable and fishable.

“Everybody should have access to clean water,” said Adam Lindquist, vice president of environmental initiatives at the Partnership. “That’s what the Clean Water Act said back in 1972, and it’s because there’s so many benefits to being out on the water and being out in nature.”

Baltimore’s Inner Harbor may have a trashy history, but with key water quality indicators improving across the waterway, Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore is advancing plans for recreational water trails and, in the future, swimmable areas. Water trails are clearly marked paths of waterway for people to paddle, kayak, canoe, or participate in other recreation. By winter 2023, the Partnership expects to release the plans for the Baltimore Blueway, a connection of these trails across a large portion of the Harbor.

“The water in this tidal basin literally connects every one of us together,” said Chris Streb, an environmental engineer at Biohabitats, the company designing the Baltimore Blueway water trails, “and therefore the goal of a swimmable and fishable Harbor is more than just about improving the environment – the higher purpose is realizing this vision is really a signal of all of working together to make this happen.”

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott is a kayaker, so he treasures the Harbor’s recreational opportunities.

“It’s not just for someone like me who loves to kayak – if you didn’t know that’s how I made it into the Fourth of July fireworks, via kayak, it drove my security team nuts,” Scott said to an audience of press and environmentally minded residents at the release of the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore’s annual Harbor Heartbeat report card on Oct. 6.

“This work is going a long way to ensure that people who visit the Harbor will actually have the opportunity to engage in activities that help fully utilize this most special place in our city,” Scott said.

Then and Now

In terms of recreation, the history of Harbor health is centered around two major issues: unsightly trash pollution and sewer pollution, which make the water dangerous for humans. These clearly visible, and smellable, issues have seeped into the community’s perception of the Harbor and led many to scoff at the idea of Harbor recreation. While there is still work to be done, nonprofits and government officials are celebrating massive improvements.

For the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, all of this work has been focused on reaching the swimmable and fishable status.

“The harbor has good days and bad days,” Lindquist said. “If it hasn’t rained for a while, the harbor is safe enough to swim in. But when it rains, pollution washes off of our surfaces and gets carried into our waterways and just like anywhere in the Chesapeake Bay you wouldn’t want to swim for 48 hours after a rainfall, the same is true in Baltimore.”

Trash

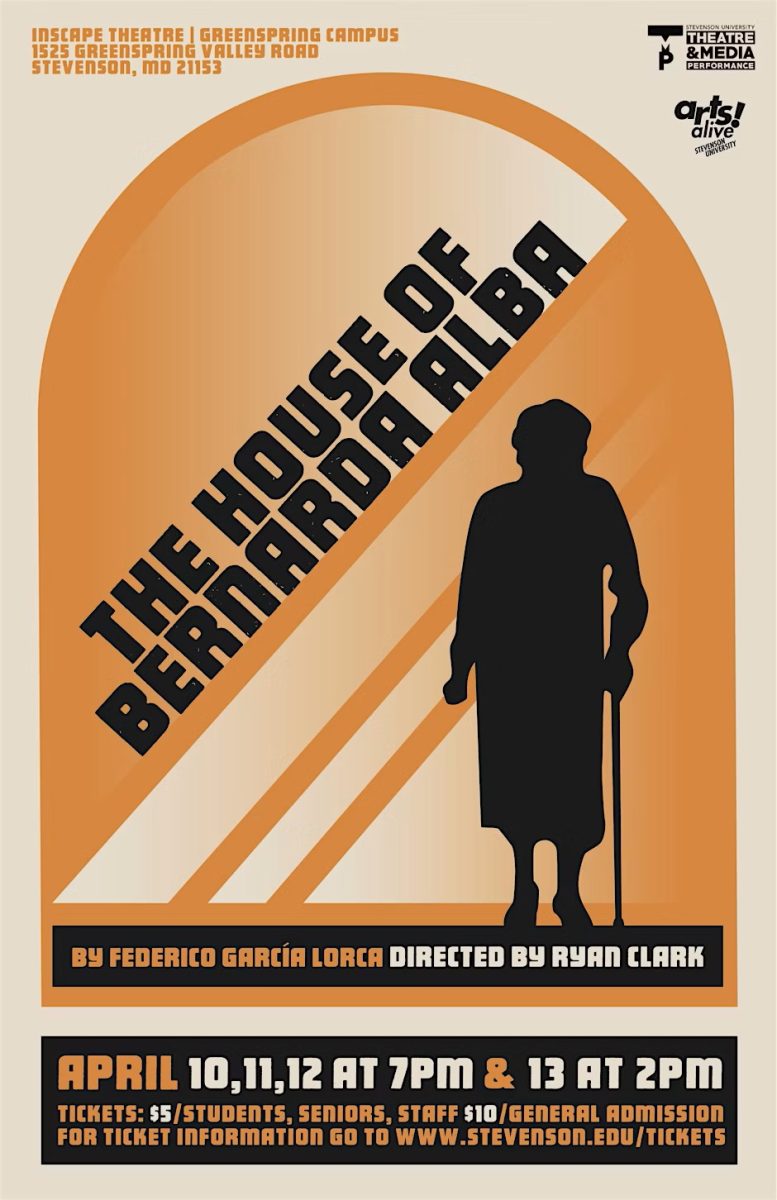

Students at Stevenson University rush to get to class while others linger and talk with friends on the Dell Pathway connecting the school’s North and Main Owings Mills campuses. This bridge passes over the Gwynns Falls stream, which will eventually flow into the Harbor, according to Dr. Mark Norris, a biology professor at Stevenson University. Any trash bobbing along the current or stuck in nearby brush will make its way downstream until it reaches whatever final destination it has in sight.

Trash can enter the Harbor in a few different ways, from rain sweeping litter from City streets, to garbage flowing from the waterways that dump into the Harbor. Trash was a “major problem,” according to the Partnership’s first annual Harbor report card in 2010, and after years of collection methods with various success rates, the City implemented a much cuter, long-term solution — a googly-eyed water wheel that simultaneously collects waste and produces energy.

Almost a decade after Mr. Trash Wheel was installed in the Jones Falls stream, the family of now four, trash interceptors has collected over 2,000 tons of waste from the Harbor’s waterways, according to the 2022 Harbor Heartbeat report. This measure, in combination with street cleaning and legislative action like plastic bag and foam container bans, has reduced the garbage entering the Harbor.

Recreationalists are taking advantage of these dramatic improvements, keying up for the Baltimore Blueway network of water trails. Chelsea Anspach, a paddler and the communications manager at Healthy Harbor Initiative, said, “there’s never any trash when I go. It surprises a lot of people who haven’t paddled in the Harbor because there’s such a bad rap.”

Sewer Pollution

The Baltimore Sun called it a “powerful stench” in 2012, a Redditor in the r/Baltimore subreddit commented “Absolutely horrible. My nose is burning” in 2014, and a Tripadvisor reviewer described the water as “disgusting and smelly” in 2018. Sewer overflows not only directly impact the safety and smell of the Harbor, they also impact the water ecology, leading to algae blooms, which also smell and have ecological impacts of their own, according to the Harbor Heartbeat.

“The problem with the sewer system — and this is not unique to Baltimore, this is a very common problem in a lot of cities — the sewer system was built over 100 years ago as the cities were built and expanding,” Dr. Norris said. “100 years ago, Baltimore had a state-of-the-art sewer system, but as the city continued to grow, and that system continued to get older and older, pipes deteriorated and became leaky and overtaxed, overused.”

When it rains (rain is the pesky culprit once again), water enters the leaky pipes and leads to overflows, flushing fecal matter into the waterways and contaminating them with bacteria and a strong odor. In response to this issue, Baltimore City Government “modified an agreement with regulators to prioritize repairs to old sewage infrastructure and eliminate releases of sewage into our waterways,” according to The 2019 Baltimore Sustainability Plan prepared by The Baltimore Office of Sustainability.

The City funded a major sewer-realignment project in 2021, and “the Baltimore City Department of Public Works reported a 64% reduction in sewer overflows by volume,” according to the 2022 Harbor Heartbeat report. “Sewer overflows have dropped by an additional 90% during the first half of 2022.”

That’s a big deal for both the broader ecosystem, and for those who use the Harbor for recreation. Companies like B’More SUP (Stand Up Paddleboarding) and Canton Kayak Club, which both offer classes and rentals in the Harbor, have a lot at stake when it comes to water safety. Jessie Benson, the owner of B’More SUP, told the Baltimore Sun that she cancels trips that are within 48 hours of heavy rainfall, meaning her revenue is at the mercy of the weather and its subsequent impacts on water pollution.

For some, the option of Harbor recreation still seems like a fairytale. For Stevenson University student Rachel Harbert, 21, the Harbor just isn’t there yet. “With the knowledge of how Baltimore City’s sewer system works, [watersports in the Harbor is] just no good.”

Harbert, a naturalist at Marshy Point Nature Center and certified canoe and kayak instructor, is no stranger to questionable water.

“As somebody who is willing to do watersports in water that isn’t necessarily super clean, I still would go nowhere near the Harbor,” Harbert said. “I am 100% down with kayaking and paddleboarding in Back River, which a lot of people are super hesitant to do — I don’t have a problem with that, but you won’t even catch me in the Harbor.”

The City and nonprofits like Waterfront Partnership are committed to getting the Harbor to a place where more people feel comfortable and excited to utilize this resource. That’s a big personal motivation for the Waterfront Partnership’s Lindquist.

“I love kayaking, and when you kayak you see a lot of wetlands, but kayaking in Baltimore City, seeing the urban shoreline, paddling alongside Mr. Trash Wheel, it’s just such a fun experience, and I just want to bring that experience to more people in Baltimore City,” Lindquist said.

Harbert hopes it gets there soon.

“I would be open to [watersports in the Harbor] if it ever reached that point [of safety]. That’s definitely something that I would love to see in my lifetime — I don’t know if it is possible but if it is, then you will catch me out there on a paddleboard — I’m 100% open to doing that.”

The health of the Harbor is a priority for Baltimore City government, and recreation opportunities have potential for economic and community development, and for increased environmental stewardship.

“You don’t care for a place if you’re not connected to it,” Norris said, “and so having access to those resources, hopefully helps build those connections, establishes relationships and then fosters care for the resource, for the community, for the city.”

Biohabitat’s Streb said, “What the Baltimore Blueway really requires is that shift in our perspective of what the Baltimore Harbor is — it’s more than a port, it’s more than an industrial waterway. And if we can imagine a Harbor as this open space – as a recreational amenity, a cultural and ecological resource,” then the view from Bond Street Wharf may soon be spotted with many more recreationalists in brightly colored equipment, enjoying that unhurried pace.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Stevenson University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.